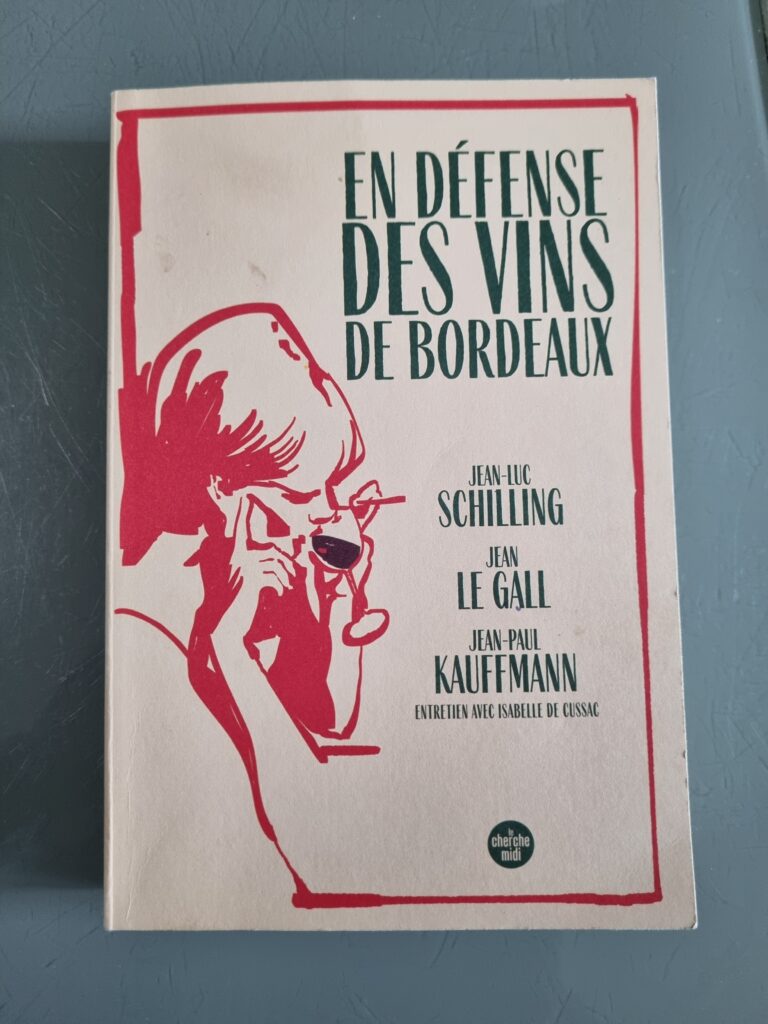

En Défense des Vins de Bordeaux

by Jean-Luc Schilling, Jean Le Gall, and Jean-Paul Kauffmann (interviewed by Isabelle de Cussac)

Published in 2024 by Cherche Midi, 312 pages, 21.90 € (or 14.98 € in Kindle format)

Bordeaux Bashing has been going on for some twenty years and sprang from a variety of causes, many unquestionably the fault of the Bordelais, but others due to outside factors or, indeed, to bad faith on the part of detractors.

This book is in three parts. I found the first one, written by Jean-Luc Schilling, who had already written Eloge Immodéré du Vin de Bordeaux published in 2018, to be the most insightful and interesting. His contribution is learned, witty, pugnacious, and thought-provoking. The middle part gives an overview of why Bordeaux Bashing developed, without much depth or innovative analysis. It is nevertheless worthwhile to those who had little understanding of the subject. The last part, an interview with journalist Jean-Paul Kauffman, shares the thoughts of someone long-associated with Bordeaux. Kauffman, the founder of the now-defunct Amateur de Bordeaux magazine, achieved nationwide attention when he was held hostage by Lebanese terrorists for over two years in the 1980s. He famously survived captivity with his sanity intact by reliving his many experiences with great Bordeaux over the years and remembering château visits, winemakers, memorable meals, etc.

The authors trace the start of Bordeaux Bashing back to two things. The first was John Nossiter’s movie Mondovino (2004), in which the Bordelais – as opposed to the genuine, well-meaning, hard-working winegrowers elsewhere – are presented as frivolous, condescending, and entitled. The friendly Burgundians get their hands dirty, drive tractors, and even stomp grapes in their underwear while the Bordealais wear three-piece suits and are light years away from the nitty-gritty of wine production. The movie was a considerable success internationally. On the French scene, two widely-viewed television programs, Cash Investigation in 2016 and Cash Impact in 2018 stigmatized the environmental damage done by pesticides in Bordeaux, strangely not mentioning any other vineyard region.

This is one of the reasons that organic and so-called natural wine caught on in France and abroad.

En Défense des Vins de Bordeaux unsurprisingly sees things largely from a French perspective. The perpetual dichotomy between the great growths and the other 95% of Bordeaux is unfortunately not sufficiently examined. The fact that nearly 10,000 hectares of vines have recently been uprooted is only briefly touched upon, with a grudging acknowledgement that many of these were not planted on the best terroirs and that quality on the whole will be improved as a result.

References to specific wines, as is so often the case when speaking of Bordeaux, tend to focus on the élite estates. Of course, the erratic pricing of these has legitimately put off many consumers who, reminiscent of Aesop’s “Fox and the Grapes”, turned away or even bad-mouthed wines they could no longer afford, or afford as easily.

In many quarters, especially among the young, Bordeaux acquired a stuffy bourgeois image, a wine their grandfather drank. Meanwhile, of course, other regions all over the world began producing increasingly worthwhile wines that were upfront, fruity, uncomplicated, and inexpensive.

Robert Parker necessarily turns up in all three parts of the book, which recycle the usual myths (Parker “discovered” the 1982 vintage, he is the reason behind “uniform over-oaked and over-extracted wines”, his “unhealthy relationship” with Michel Rolland, etc., etc.). Credit is nevertheless given to Parker, who commanded a position that no critic has ever equalled since. He is especially recognized as having turned Americans on to Bordeaux.

Sadly, as with most other wine regions, the present economic conjuncture is not conducive to sales of Bordeaux. Declining consumption of red wines (90% of production in Bordeaux), can be contrasted with increased sales of whites and rosés. And neo-prohibitionism has reared its ugly head… Meanwhile, climate change calls for different viticultural practices, winemaking, and even new grape varieties. What to think of Bordeaux weighing in at 15+ percent alcohol?

One of the powerful messages in this book is that it is wrong to consider Bordeaux self-satisfied and resistant to change. In fact, the region is tremendously dynamic and always has been. How else can you account for the millions of bottles exported all over the world every year?

Another theme, perhaps the most important of all, is the idea that, despite what anyone says, Bordeaux is a classic wine, a byword for elegance, balance, and ageing potential. It will never go out of style. Bordeaux need not blush when compared with wines from anywhere else, and that includes the medium price range. Trends come and go, but a great Médoc or Saint-Emilion represents eternal values that will survive the roller coaster reality of supply and demand.

Buying wine en primeur and waiting 20 or 30 years to drink it may seem contradictory with the 21st century lifestyle. But there are enough discerning wine lovers around the world to perpetuate the tradition, and always will be. Sadly, the book takes only a cursory look at the predicament of the lesser, everyday wines of Bordeaux. But this is forgivable because no one has an easy answer here.

En Défense des Vins de Bordeaux is a quick read in easy-to-understand French. It is a welcome addition to my library of wine books, if not an essential one.