This post will be as much about tourism and cuisine as it is about wine because these three things are inseparable to me when it comes to Madeira.

I went there with my family at the tail end of December 2018. In fact, this trip to one of the world’s great wine regions had been on my bucket list for quite some time. Fortunately, I was not disappointed with the experience: the island, the people, and the wines.

The first thing to keep in mind is that Madeira is a long way from anywhere – almost 1,000 km from Lisbon and 600 km off the Moroccan coast. The island (in fact, one big island and three little ones) is a popular tourist destination, with about a million visitors a year. Although many of them come on cruise ships, the overall impression I had was of relatively up-market tourism involving people who go out of their way to discover a unique 750 km² sub-tropical paradise. In fact, Madeira is nicknamed the “island of eternal spring” because the weather is never too hot, nor too cold.

We stayed in the capital city, Funchal, population 110,000.

The first evening, we went to a restaurant named “Beef and Wine”, where we ordered the house speciality, espetada. This is usually chunks of beef but, in this case, it was actually a variation, picanah, top sirlon rubbed in garlic and salt, and grilled on skewers. The waiters come around as many times as you wish with their skewers, like the Brazilian churrascaria. The meat was served with a variety of vegetables. I took advantage of the extensive wine list to try a local red table wine, 2013 Xavelha, made from a blend of Portuguese and international grapes. This proved to be a good middle-of-the road effort. I later learned that table wines are quite rare, accounting for just 5% of production. We ended the meal with two glasses of ten-year-old Madeira, a Sercial and a Verdelho from Barbeito. I had heard very good things about this producer, but unfortunately was unable to visit because the firm was closed over the Christmas season. Be that as it may, the two wines we tried were delicious, in a more modern style.

- Traditional breadmaking

- bolo do caco

We also enjoyed the unusual Madeiran bread, bolo do caco, usually served with garlic butter.

- Rubina Vieira

The next morning, I was taken in hand by the IVBAM, or Instituto do Vinho, do Bordado e do Artesanato da Madeira, IP-RAM. I was greeted by Rubina Vieira, who does a wonderful job of presenting a wine that most people have heard of, but few know much about… Rubina started off by putting the wine in a historic context – its more than 500 years of ups and downs, as well as its current market status. A famous story goes that the Duke of Clarence, brother of King Edward IV of England, when sentenced to death for treason in 1478, chose to meet his creator by drowning in a butt of Malmsey. Indeed, Duke of Clarence is the name of a wine sold by Blandy’s, one of the largest producers of Madeira! In Shakespeare’s “Henry IV”, Falstaff sells his soul to the devil “for a cup of Madeira”. Later on, Madeira found great favor in Europe and especially the United States, where the Founding Fathers used it to toast the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Exports were greatly helped by Madeira’s strategic geographical location, a stopover point on trans-Atlantic voyages. It was soon discovered that the wine benefitted from being stored in the warm holds of ships, and so a practice developed of imitating this effect on the island. This is achieved in two ways. The most common is the estufagem method, consisting of placing the wine in stainless steel vats that are heated with a serpentine or other kind of heating system to a maximum temperature of 50°C for a minimum of three months. The wine is then left to age and cannot be bottled before the 31st of October of the second year following the harvest. The more sophisticated canteiro method calls for maturing in barrels on the top floors of cellars, where the temperature is higher, for a minimum of two years. This leads to slow oxidative ageing accounting for unique, complex aromas. Canteiro wines must age for at least three years and can only be sold after a minimum of three years starting from the 1st of January of the year following the harvest.Madeira has an alcohol content of 17-22% by volume and is fortified with wine spirit of at least 96% (compared to Port’s 77%).

Much Madeira is marketed according to style (dry, medium-dry, medium-sweet, and sweet) but the finest usually carry a varietal name:

Sercial is nearly dry (≤ 59 g/l), but seems dry because of the wine’s intrinsic acidity

Medium-dry Verdelho has its fermentation halted a little earlier than Sercial, and residual sugar content varies from 54-78 g/l

Bual, classified as medium-sweet, has a sugar content of 78-100 g/l

Malmsey is quite sweet, with ≥ 100 g/l of sugar

The most widely-planted variety in Madeira is Tinta Negra, accounting for 85% of production, although the name rarely appears on a label. There has been a tendency to consider Tinta Negra a “workhorse” grape rather than one of the finer varieties, but a 1929 Tinta Negra I tasted showed that to be an unfair generalization. And then there is the rare Terrantez, which produces a medium-dry or medium sweet wine of excellent quality that is making somewhat of a comeback.

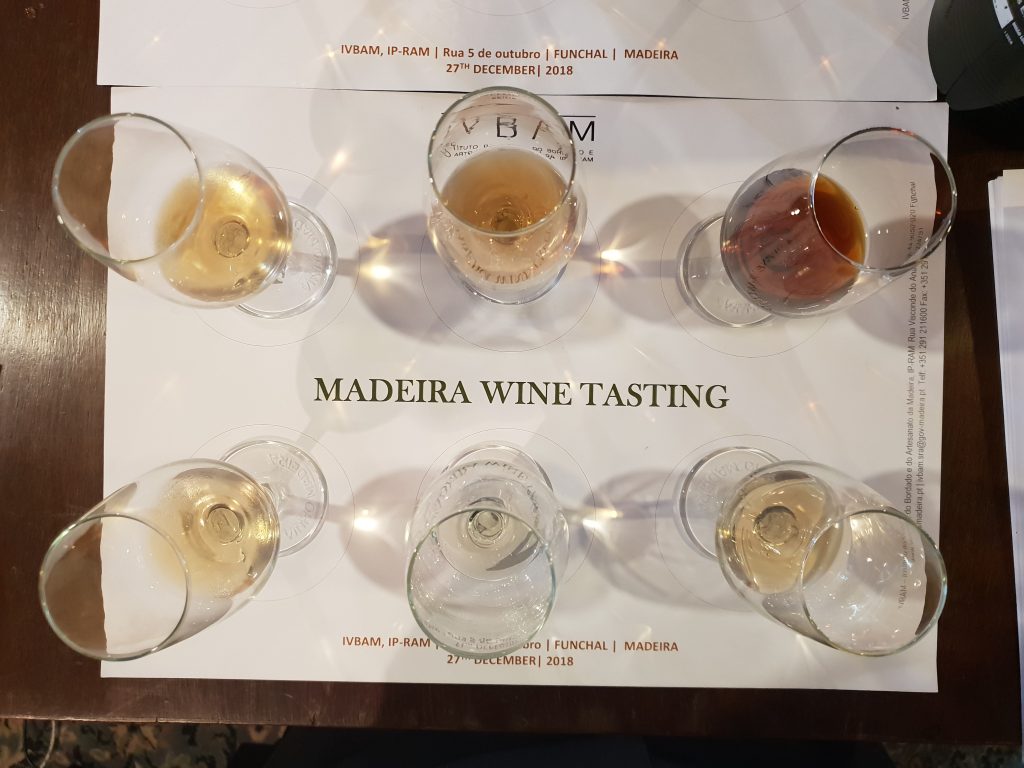

Rubina was kind enough to take me through a tutored tasting of the following wines:

CAF Cooperative Agrícola do Funchal five year old (blend)

Barbeito “Rainwater”, medium dry

Henriques & Henriques 10 year old Sercial

Borges 10 year old Verdelho

Barbeito 10 year old Bual

Justino’s 10 year old Malvasia (same as Malmsey)

Henriques & Henriques 20 year old medium dry Terrantez

1973 Madeira Wine Company Verdelho

1964 Justino’s Bual

1937 Pereira Oliveira Sercial

1929 sweet Pereira Oliveira Tinta Negra

This master class was utterly fascinating, and the older wines were gorgeous.The style called “Rainwater” is very popular in the US. It is lighter and similar in sweetness to Verdelho, but usually made with Tinta Negra. Explanations of the origin of the name and how the style developed vary.

There was a time not so long ago when extremely old Madeira could be bought for a song – in fact, for ridiculously low prices, making it one of the wine world’s greatest bargains. Those days may be over, but fine Madeira remains well worth seeking out.

The wine law was recently overhauled, and the broad categories are now as follows:·

Reserve (five years) – This is the minimum amount of ageing for a wine labelled with one of the premium varieties.

Special Reserve (10 years) – At this point, the wines are often aged naturally without any artificial heat source

Extra Reserve (over 15 years) – This style is richer and relatively rare, with many producers preferring to extend the ageing to 20 years for a vintage, or produce a colheita.

Colheita – This style includes wines from a single vintage, but aged for a shorter period than true vintage Madeira. The wine can be labeled with a vintage date, but includes the word colheita on it. Colheita must be a minimum of five years old before being bottled. However, most producers drop the word Colheita once a wine is a minimum of 20 years old, at which point it can be sold as vintage.

Frasqueira (“vintage”) – This style must be aged at least 20 years in cask and one year in bottle. However, the word “vintage” cannot appear on labels because it is a trademark belonging to the Port producers.

In France, Madeira suffers from an unusual handicap in that it is an ingredient in numerous classic sauces. Like many households and restaurants, I always have an open bottle to use in cooking. However, this overshadows the wine’s qualities in its own right… That having been said, Rubina pointed out what I had heard elsewhere: while Port and Sherry, the other great European fortified wines, are losing ground, exports of Madeira are on the rise.

The sugar content of Madeira, including dry Sercial, is actually quite high. This is because the wines feature such high acidity that sweetness is necessary to provide proper balance.

The IVBAM was kind enough to take me on a tour of the wine country, guided by Lionel Vieira, the Institute’s viticultural consultant. This was utterly fascinating and something I could never have done on my own.Rubina stressed that Madeira is by definition a rare wine. The entire vineyard covers just 500 hectares (compared with 650 hectares in Pomerol, practically the smallest of Bordeaux’s 57 appellations). These are scattered around the island in one of seven microclimates and divided among some 2,000 grape growers. The soil is basically the same everywhere: basalt of volcanic origin, which accounts for the high acidity. The island is very mountainous and so the vines frequently grow on terraces located on steep slopes. The grapes are mostly trained according to the latada system, i.e. making use of a pergola 1.5 to 2 meters high. This provides good ventilation and reduces the risk of rot or mold. In times past, vegetables were grown underneath, but this practice is disappearing. I also saw something in Madeira that was quite esoteric: vines trained horizontally, i.e. with the canes spread out on the ground, with no trunk. The key here is to work the soil so as to keep the ground well-aerated and totally devoid of other vegetation.

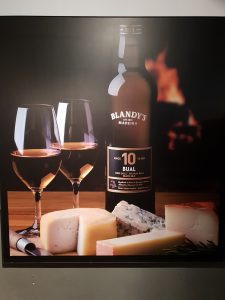

There are just 8 producers of Madeira. The largest, by far, is Justino´s Madeira Wines Company. The most well-known is the Madeira wine company, owners of such brands as Blandy’s, Cossart Gordon, Leacock’s, and Miles. The historic Blandy’s Wine Lodge, on Funchal’s main street, located practically next door to the Tourist Information Office, is a major attraction. I went on a tour there, which was well done. Unfortunately, tasting more than two entry level wines entailed a charge for each wine, so I contended myself with buying a bottle of Terrantez because this is so difficult to find.

The only other producer I visited was Pereira D’Oliveira. This traditional firm, also in Funchal, is famous for their old wines. Oliveira’s is not geared up to receiving foreign wine enthusiasts. The several young hostesses were not really clued-in and communication in English was not easy. It took some convincing to taste anything other than the basic blends. Their attitude changed completely when I was finally given a rare and expensive wine to taste, and bought a bottle. Evidently, I was not a freeloader, so other wines were poured and a few souvenir items were added free of charge…

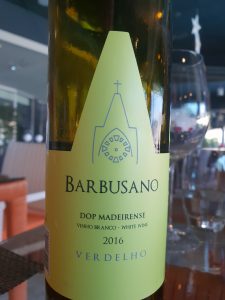

In terms of dining, allow me to go through the restaurants we frequented. Lionel from the IVBAM invited me to the restaurant at the Four Views hotel in Funchal. This included poached egg soup and the emblematic black scabbard fish with bananas and passion fruit sauce. We had another Madeiran table wine with this, 2016 Barbusano Verdelho, perhaps a bit too tart for me. Lunch the next day was at a seafront restaurant, O Regional, that provided excellent value for money as we ate outside on a warm December afternoon.

That same evening we dined at Chris’s Place, on a par with a one-star Michelin restaurant. The three of us ordered the tasting menu with wines to match and the bill came to 100 euros, representing great value for money. In addition, we enjoyed lunch one day at Cachalote in Porto Moniz on the northern side of the island, which I also recommend. I sampled a dish there revolving around limpets that went well with a white Douro wine.

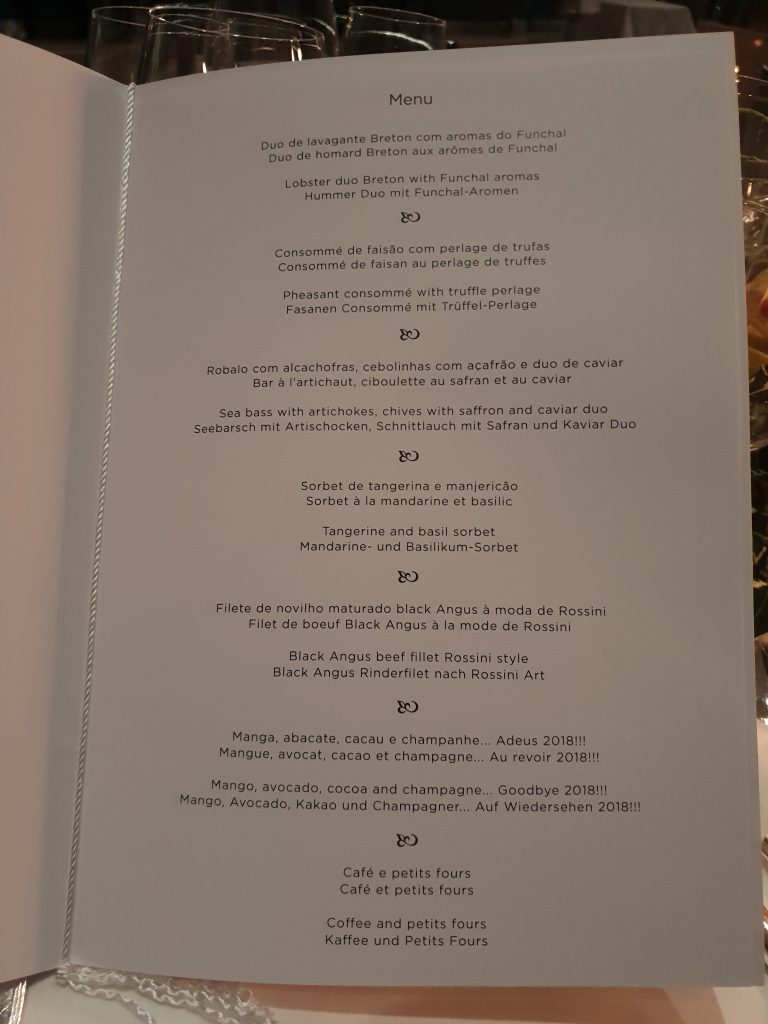

The highlight of our trip was nevertheless the New Year’s Eve gala dinner at the Belmond Reid’s Palace hotel in Funchal, an establishment normally out of my price range, but one of those luxurious things one does from time to time… The food was exquisite, as was the setting, and we had a window seat with a gorgeous view over the city and the harbour.

This mattered, because the fireworks display on the 31st of December in Funchal is world famous. There was a blaze of color all over the town and on the water. Spellbindingly beautiful.

Although Madeira is a major tourist destination, I had the impression that wine is very much of a footnote in regional promotion, which is a pity. That having been said, wine tourism is slowly, but surely taking off. Furthermore, Rubina travels all over the world to present the wines and suggest how to enjoy them with food (frequently a question mark with sweet wines). One of the unusual characteristics of Madeira is that it does not budge once the bottle is open. I was repeatedly told that you can go back a year later and it will not have suffered from contact with oxygen.

The challenge for Madeira is to close the gap between a famous name and the realities of today’s market so as to shake off a 19th century image and turn young people on to one of the world’s great wines. I get the feeling that thanks to the intrinsic quality of fine Madeira and people like Rubina to spread the good word, a renaissance is in the making.

A final anecdote: I attended a service at the Anglican church in Funchal and was delighted to see that along with the traditional tea and coffee after the service, worshipers were also given the option of a glass of Rainwater Madeira. Needless to say, that is what I chose… I found this mighty civilized and think that churches in other winegrowing regions – such as Bordeaux – would do well to offer the same!