Can a wine be accurately described as feminine or masculine?

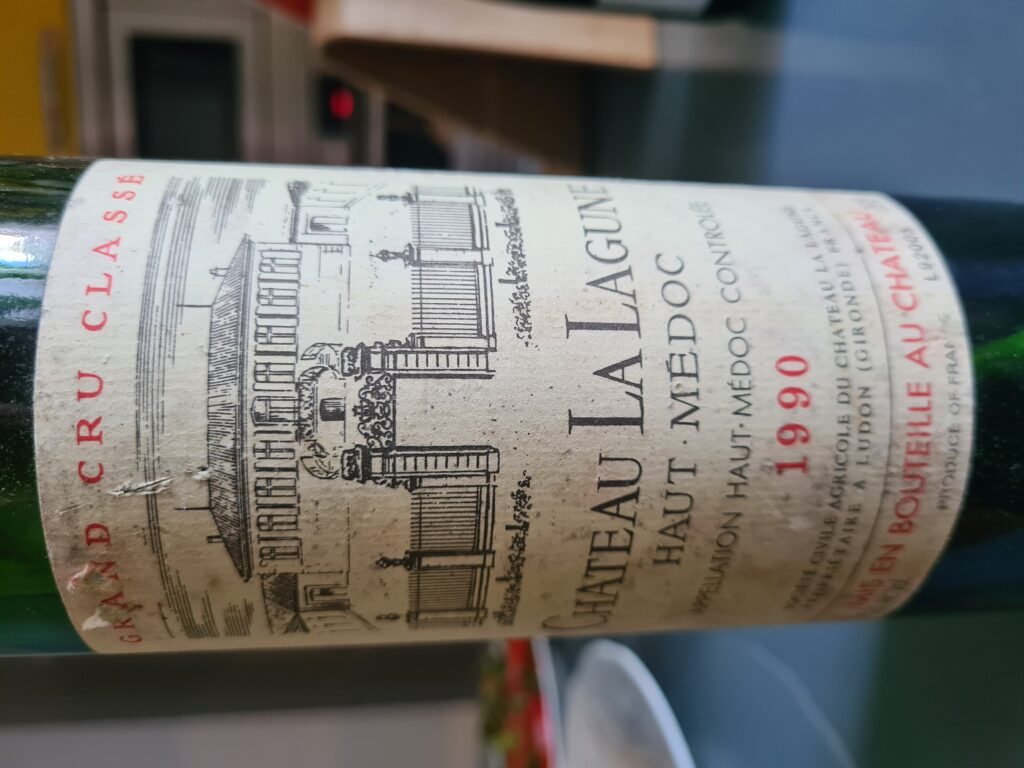

That was one of the subjects under discussion last night with my neighbors, whom I had invited over for dinner. I served a wine from Ludon, where they have family ties: 1990 Château La Lagune. This looked far younger than its years and had a delightfully evanescent nose of ripe Cabernet, humus, and truffle. The wine was suave and seamless, by no means powerful, but very elegant and poised. It was as good as it will ever be, even if I’m sure its plateau will be quite long.

It reminded me of one of the better wines of Margaux.

Anyway, although they’re from the wine country, my neighbors have only an ordinary interest in the stuff and, when I described the La Lagune as feminine, the wife was surprised. She had never heard such a reference, and it puzzled her. “Is this a usual term?” she inquired. I replied in the affirmative.

The question I’ve asked above is whether wine descriptions can be gendered in order to convey a meaningful and comprehensible message – not whether they should or should not be.

In this age of political correctness – including a movement to bowdlerize and rewrite children’s fairy tales! – there are undoubtedly people who object on principle, going on the assumption that it is wrong to ascribe characteristics to either sex (since there are strong women and dainty men, etc.). So, I will leave that issue aside. I have even heard women winemakers say that females leave a discernible feminine imprint on wines, which if I find rather hard to accept (that having been said, La Lagune has been made by a succession of women over the years!).

Getting back to semantics, and the way we speak about wines, I believe that it is both useful and going on universally understandable to describe a Chambolle-Musigny as feminine or a Châteauneuf-du-Pape as virile, a practical sort of shorthand. What is trickier is to extrapolate from those words to find out what they really mean. Would a WSET or MW student be marked down for using them? Does a woman, for example, have a different conception of what a feminine wine is than a man? Do wine lovers in Sydney and Montevideo, with different cultures and languages, agree on the characteristics of a masculine wine?

In my opinion, any wine geek or professional can relate to the description of 1990 La Lagune as feminine. Rather than lacking punch or character, those attributes are very much present, but restrained and under control – or, as Mitterrand liked to market himself, “la force tranquille”. The French say an aromatic wine is “perfumed”. That, also, can be one of the hallmarks of a feminine wine, where the aromas are subtle, yet distinctive. As for aftertaste, such wines can be long and voluptuous, but not in your face.

I once went to Château Margaux with a visiting group from the Bordeaux Wine Enthusiasts forum. I asked the late Paul Pontalier the following question “It is often said that Margaux is the most feminine of wines. Is that true and, if so, how is it true?”. There followed an exceedingly brilliant exposition in impeccable English. I very much regret that I did not record it.

And masculine wines? A big, strapping Australian Shiraz fits the bill very nicely thank you, but that is a caricature. Ch. Latour is one of the most masculine wines in Bordeaux, and yet it is a wine of great depth and nuance. In the same way that feminine wines need not be delicate, neither do masculine wines have to be big thumping ones on steroids. Still, there is the idea of full bodied, straightforward wines with above average alcohol content (although this is not defining).

I’ve heard those terms around for as long as I can remember and am confident that they are here to stay. I do feel, though, that caution should be exercised in using them and that they definitely should not be overused.