SAINT JULIEN

Beychevelle

N: Perfumed, lovely, fresh, and understated bouquet with fancy oak nuances.

P: Medium-weight showing great delicacy and delicious fruit flavors. Seems almost Margaux-like. Lacy texture, fine balance, and great acidity. Very good.

Branaire Ducru

N: Suave, but not very complex. Quite fruity with some roast coffee overtones.

P: Not full-bodied, but tasty, with marked acidity. More tannin than Beychevelle, but not quite up to its quality. Good.

Ducru Beaucaillou

N: Sweet, subtle fruit, the expression of fine Médoc through the ages.

P: Dense, resonating fruit and considerable concentration. Powerful ripe Cabernet character with some black olive nuances. Extremely long aftertaste. Very good.

Gruaud Larose

N: Very classic, very Cabernet nose with some pencil shaving aromas. Fresh and attractive, but I was hoping for more…

P: Rich cassis flavors with a good texture, going on to show acidity, then minerality. Not particularly well-balanced. The sudden drop disappoints. The degree of acidity means the wine will age well but it lacks richness, body, and if the truth be known, fruit for its standing. Nevertheless good.

Lagrange

N: Very reserved, a little smoky, and already leads one to believe the wine may be lacking in concentration on the palate.

P: Starts out relatively full-bodied, then goes into acid mode. Will age well thanks to this, but will always remain a little hard and a little short. Good.

Langoa Barton

N: Soft, sweet bouquet, but not very concentrated. Oak is in the background.

P: Seems chunky at first, but then fresh piercing acidity shows through. Classic blackcurrant notes, but the range of flavours is relatively narrow. Somewhat thin on the finish. Good.

Léoville Barton

N: Strong cedar aromas to match the fruit. Both classic and charming.

P: Silky/satiny texture with good concentration. Showing plenty of blackcurrant, and enough body to back up that 2017 acidity. Very long and dry (not negative here) aftertaste. Streets ahead of Léoville Poyferré. Very good.

Léoville Las Cases

N: All the hallmarks of the château with fresh, mythical blackcurrant nose.

P: Great velvety texture and develops beautifully on the palate. Both sensual and mineral. Tremendous finish. In no way can this be considered a poor or even middling vintage for Las Cases. Very good.

Léoville Poyferré

N: Not very expressive, but inevitable blackcurrant and tobacco aromas.

P: Seems both soft and a little diluted. Does not spread out on the palate as hoped. Lacks body and richness. Somewhat redeemed by a long and fairly mineral finish. Needs re-evaluation later on. Good.

Saint Pierre

N: Sweet upfront bouquet with toasty oak. Charming and immediately attractive rather than deep.

P: Some richness there and lots of fruit and, once again, oak. This needs to integrate. A more modern style, but one that suits both connoisseurs and people with less experience. Fine, tangy aftertaste superior to many other classified growths in Saint Julien on this day, and perhaps less acidic. Good to very good.

Talbot

N: Rather closed. Not much fruit showing at present, but with some cedar notes.

P: On the thin side for a Saint-Julien though it will undoubtedly put on weight and mellow out with age. Definitely not a great Talbot, however there is a nice long aftertaste with some black olive nuances. Good.

PAUILLAC

d’Armailhac

N: Pretty, perfumed, even a little cosmetic (in a positive way – elegant and under control).

P: Lovely, rich, and generous, going into that 2017 acidity, but still very fine. Medium-bodied. Tarry and slightly mineral aftertaste with plenty of oak. I was not alone in thinking that this is a rare instance in which d’Armailhac is better than sister château, Clerc Milon. Excellent.

Batailley

N: More developed than most with intriguing red berry (raspberry) fruit. Some earthiness, a touch spirity and a little green.

P: Spherical, but hollow and short. More commercial style than sister château Lynch Moussas, and also less good. Lots of tannin and oak here. OK to good.

Clerc Milon

N: Roast coffee notes and a little spirity. Withdrawn and less refined than d’Armailhac.

P: Better on the palate. Richness gives way to acidity. On this day d’Armailhac outclasses Clerc Milon, but what will things be like in the long term? Good to very good.

Croizet Bages

N: Fruit in minor mode, but attractive and fresh. Fine, if restrained blackcurrant nuances along with new oak.

P: Medium heavy mouthfeel. Starts out fresh, with decent fruit, but a little watery and then dips before going into an aftertaste with textured tannin and plenty of oak. This may very well integrate over time. Croizet Bages is on the upswing. About time too… Good.

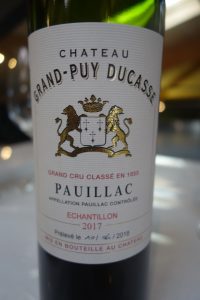

Grand Puy Ducasse

N: Unfocused, with fermentation aromas and a bit of a stink. Showing poorly, which just goes to show how tasting these wines at such an early stage can give a false impression.

P: Very acidic and frankly poor at this stage. Not up to cru classé standard. To be fair, needs to be re-tasted later on.

Grand Puy Lacoste

N: Subdued, but good potential there.

P: Rich, round, and much, much more expressive on the palate than on the nose. Lovely development. “Sweet” without asperity. Fine red and black fruit flavors. Not too much acidity, oak, or anything else really. Good to very good (if the bouquet comes out).

Haut Bages Libéral

N: Not a great deal there, just some blackcurrant leaves.

P: Starts out rich and showing medium-heavy mouthfeel, but then seems somewhat on the thin side. Fine flavour, and plenty of good acidity as it develops on the palate. Really good balance. In fact, significantly better on the palate than on the nose. A nice surprise. Very good.

Lafite Rothschild

N: Trademark violet nuances with some lead and plum aromas. Fresh and dashing.

P: Quite tannic, but tannins of exquisite quality. Not particularly rich, and presently holding back, but will be a great bottle. Lafite defies trends and changes little – because it doesn’t need to. Excellent.

Latour

N: Aromatics are low key now, but that apotheosis of Cabernet on gravel soil is all there and needs just time.

P: From the attack and up until the aftertaste, this was not particularly impressive. However, the finish is nothing short of tremendous. Medium bodied and very juicy. A baby born under a lucky star needing only to fill out and develop.

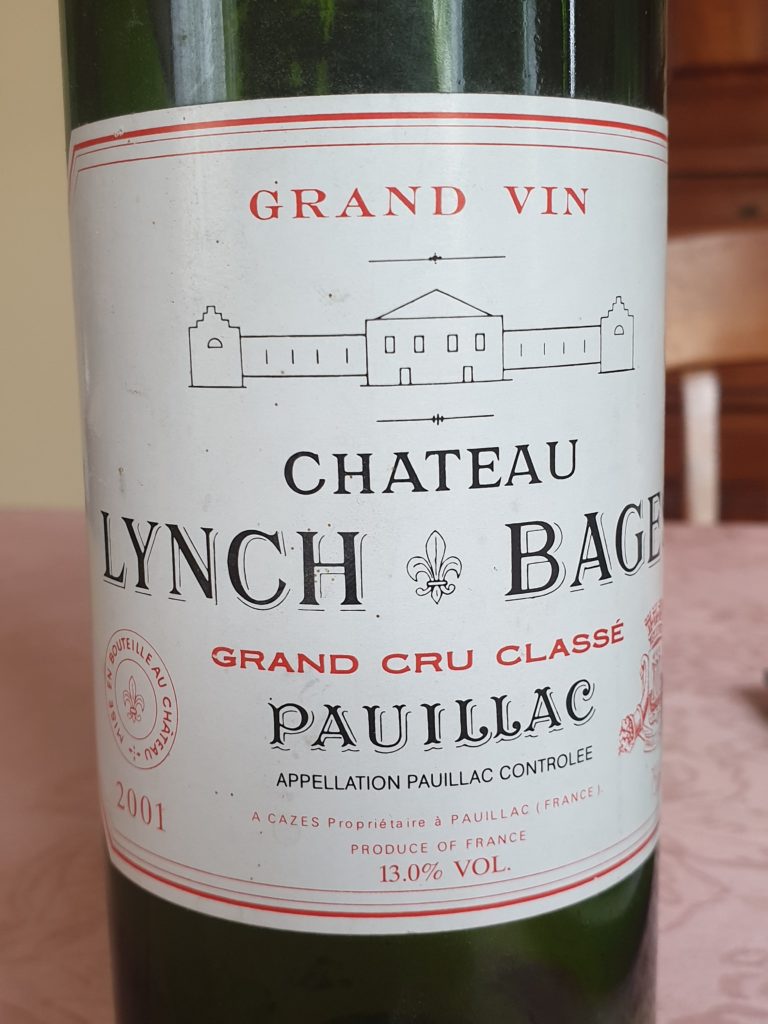

Lynch Bages

N: Fine, ripe blackcurrant nose with some emerging cedar notes. Promising.

P: Round, then sinewy. Lovely satisfying aftertaste with well-integrated oak. Good acidity. Classic wine in a good, rather than a great vintage. Rich, vigorous fruit and acidity is under control, as is the effect of barrel ageing. Very good.

Lynch Moussas

N: Interesting floral as well as ripe, slightly candied, and jammy black cherry notes.

P: Easy-going and rich on the palate. Melts in the mouth and is then followed up by ripe tannin, complemented by new oak that it just a little too harsh on the finish. Perhaps a little light for a Pauillac but a very good effort and a pleasure to discover. An estate that deserves to be better known. Good to very good.

Mouton Rothschild

N: Oak, graphite, cigar box, and deep fruit.

P: Medium-heavy mouthfeel and the lead/graphite component on the nose comes through, followed by great fruit and that acidic component so common in 2017. Virile, velvety, and aristocratic aftertaste. Tremendous length. A stand-offish Mouton, but by no means a poor one, and should age well. Excellent.

Pichon Baron

N: Super elegant nose, clear, pure, and rich. Complex and very promising.

P: WIldberry and blackcurrant flavors. The only drawback is the lack of oomph on the aftertaste. And easy-to-drink even slightly dilute Baron – that is until the finish, which features the requisite high-quality oak and tannin. Tasted just after the Comtesse, I confess I preferred the female. Still: very good.

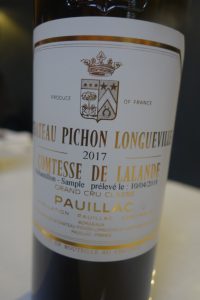

Pichon Comtesse

N: Soft, straightforward black fruit. Good, but nothing special at this stage.

P: Fairly heavy mouthfeel. Rich, sensual texture going into an aftertaste with plenty of smooth tannin. Finishes with fine, sweet fruit. Everything is in place and the wine is extremely well made. Very good and a potential star when the nose starts delivering. I often prefer the Baron, but not in this vintage or, should I say, at this point in their life cycle. Very good.

Pontet Canet

N: Juicy, soft, and a little musty, with subtle candied fruit aromas. Very enticing.

P: Fresh, with excellent structure. Straightforward, with a fine tannic backbone. A delicate balance and great finish. Long mineral aftertaste. Very good.

SAINT-ESTÈPHE

Calon Ségur

N: Dark fruit and a little beeswax, but not very expressive at this stage.

P: Fairly heavy mouth feel. Dense, penetrating and very Cabernet Sauvignon. Lovely, long, persistent aftertaste with good acidity as opposed to others in this vintage with more shrill acidity. Very typical of its appellation and estate (…so different from Cos). One for the long haul, but with charm even so. Very good.

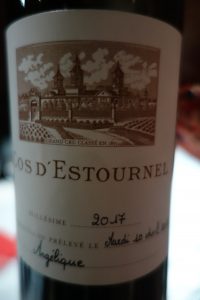

Cos d’Estournel

N: Penetrating black fruit aromas with some roast coffee overtones.

P: Sleek and well-made. No longer flirting with a bigger, more modern style, this Cos shows great class with superb tannin. Very good.

Cos Labory

N: Soft, ethereal Cabernet fruit with interesting nuances.

P: Richer than expected on the palate, but goes into an aftertaste that is not only strong, but rather rustic. Somewhat harsh finish. OK.

Lafon Rochet

N: Very closed at present, but with underlying classic Médoc nuances and a little earthiness.

P: Fresh, vibrant, and refreshing and with some weight on the palate. Lovely fine-grained tannin, but lacks some richness and there is a certain hardness there. However, the estate’s profile comes through beautifully on the aftertaste. An elegant Saint-Estèphe, as always. Good to very good.

Montrose

N: Lovely coffee, violet, and ripe black fruit aromas. Serious, complex, and very pleasing.

P: Medium-heavy mouth feel, moving forward towards a rather unyielding, but very promising aftertaste. Fine ageing potential. Very good.

(I usually don’t include notes on second wines and associated estates, but I’ll make an exception here because the other Bouygues estate in Saint-Estèphe, Château Tronquoy Lalande, was particularly successful in 2017 and this is now a wine deserving of special attention).

Ormes de Pez

N: Fine marriage of fruit and oak and clearly above average thanks to exuberant red fruit (rather than black fruit). Not intense, but expressive and appealing.

P: Relatively heavy mouth feel. Fresh and straightforward. Fine, pure fruit. Good tension and tight tannin. Very good.

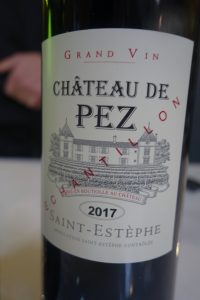

de Pez

N: Fresh and restrained, with black fruit overtones and medium body, with the oak influence under control.

P: Marked acidity and a bit mean on the finish, but should age into a decent lightish (for Saint-Estèphe) wine. Good

Phélan Ségur

N: Odd, slightly synthetic nose backed up by some leathery notes. More unusual than good or bad…

P: Better on the palate, showing some richness to start out with, but also some sharpness thereafter. The tannin coats the mouth. Good, medium-term ager. Well-made, although perhaps a little too much tannin in light of its body. Good.

![PO-2017[1]](http://www.bordeauxwineblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/PO-20171-781x1024.jpg)