To paraphrase a quote by Mark Twain, upon seeing his obituary in the newspaper “Reports of the en primeur system’s demise are greatly exaggerated

Here’s a well-written and thoughtful article:

https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2020/03/a-modest-proposal-for-bordeaux-release-the-2019s-next-spring/

It doesn’t take a genius to see that the Bordeaux’s en primeur system, like so many sectors of the globalized economy, has taken a bad hit due to the corona virus. I have seen predictions for decades that the system would crumble or implode. And yet, it has survived through thick and thin – copied, but never equalled J.

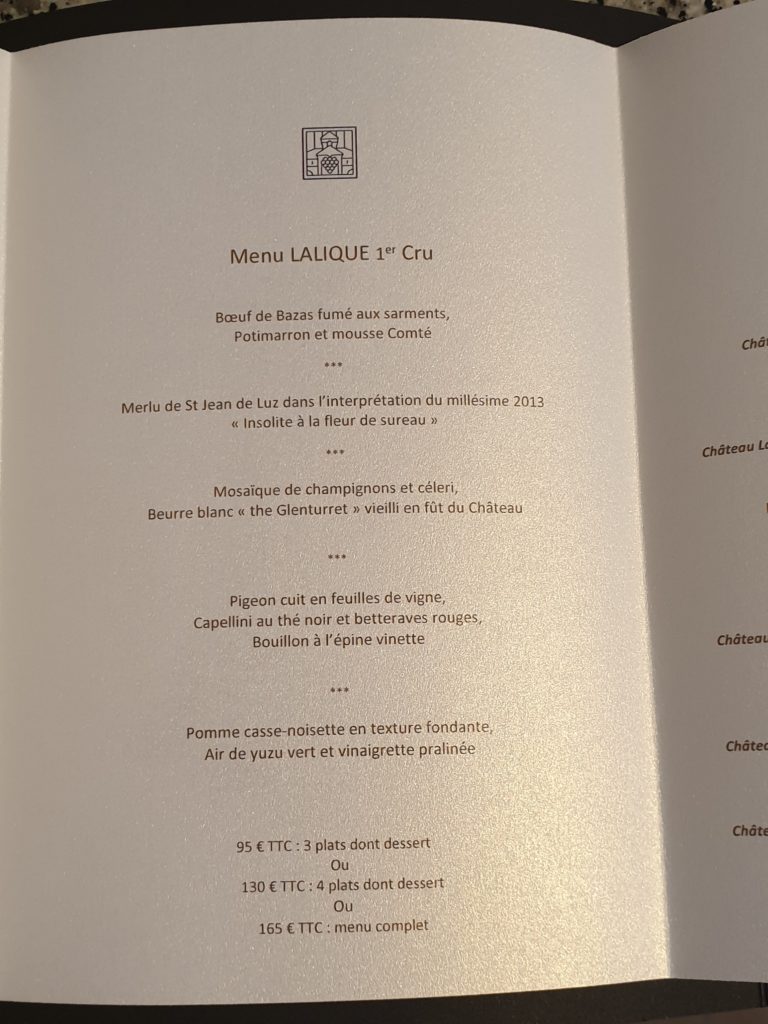

Still, the current threat is like no other and the timing of the upcoming campaign has been completely thrown off course. Wine merchants obviously cannot be expected to buy wines that no one has sampled, even though, if one is honest, the Union des Grands Crus tastings in late March/early April can hardly be seen as essential to buying… Wholesalers and importers are far more inclined to purchase based on a château’s reputation or what leading critics say rather than their own impressions. En primeur week comes across predominantly as a networking and information gathering exercise (plus the occasion to enjoy a lot of good meals!). It is nevertheless a brilliant and unique way of coordinating the whole region and arousing interest from all over the world.

I take exception to so much that is written about the en primeur system because pinning down figures – to be specific – is very elusive, and it is nearly impossible to generalize since the situation varies from estate to estate. Only the brokers based in Bordeaux are qualified to have a valid overview because they are in touch with all the negociants and thus alone feel the pulse of all international markets with any degree of accuracy. People living in London or Tokyo or wherever extrapolate from their (possibly entirely correct) analysis of the situation in their country, thinking that what they’re seeing is the same around the globe when, in fact, it is not.

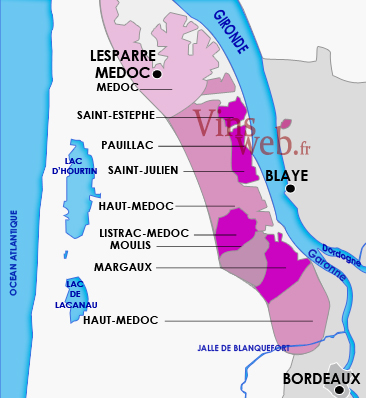

Two Bordeaux châteaux in the same appellation with the same classification can have very different commercial strategies. By the same token, two adjacent European countries can have very different markets. And you cannot lump Wuhan and Edmonton together.

Furthermore, there is not just one way of selling en primeur, which is why so many commentaries cannot be trusted. When one reads that château such-and-such “came out” at such-and-such a price, that information can paint a totally wrong picture. Some of the top châteaux release in “tranches” and the first one can cover just a very small quantity and at a particularly attractive price just to “test the water”. The first tranche offerings of famous classified growths are immediately snapped up as soon as they are put on the market because everyone knows that further tranches will be more expensive. Therefore to say that this is the base price is extremely misleading.

The proportion of wine sold per tranche and, indeed, that which is kept back for sale at a later date varies tremendously.

It seems to defy logic when en primeur prices exceed those of the same wines from a better-reputed year with some bottle age.. This can only compute if seen as part of a very long, complicated distribution chain and the allocation system that functions all down the line to the consumer. This entails a sort of threat: “If you don’t buy this year, you won’t get any next year, or from now on”. The result of this is that so-called off vintages are often dumped, and the loss is accepted more or less philosophically. Voices are raised to say that this is wrong and cannot go on because it defies the laws of economics. Certainly, a series of lacklustre vintages – not to mention a worldwide recession/depression – would force estates to lower their prices, even dramatically. But that would in no way threaten the en primeur system. Adjustments, perhaps even painful ones, would be made. Period.

President Calvin Coolidge famously said that “The business of America is business”. The same attitude prevails in Bordeaux. While the supposed greediness of the Bordelais is frequently denounced, the châteaux are also willing to react quickly, and to pay the piper, should things work against them. It’s as simple as the law of supply and demand…

It is interesting to see the comparatively little whinging about price increases in Burgundy.

Is any other wine region as vintage-conscious as Bordeaux? It is not at all rare to see wines from the same château double (or halve) in price from one year to the next. The market for Bordeaux great growths is indeed volatile! Their price is quoted daily and, in some instances hourly, on the internal market, the “place de Bordeaux” accessible only to négociants. This is a complex reality and it takes a brave man, or a fool, to make across-the-board statements about it.

The article cited at the beginning of this post touches on a number of worthwhile points. I would only take issue with the timing of the proposed 2019 campaign. I think it would be better in September 2020 than the spring of 2021. I agree that March is not the ideal time to taste the great wines. September would make a more realistic evaluation possible as well as give buyers an idea of the volume of the future crop and, to a certain extent, its quality. The author of the article says that September is not good because great wines from other regions are released then. If that is true, I would appreciate knowing more about this. I do not agree that there would be a lack of interest because of lead-up to the Christmas season. Early September would be fine in my opinion since the harvest would only theoretically have just begun for dry white wines, accounting for only a fraction of Bordeaux’s production. If September were chosen, it would be wonderful if the tastings and campaign stayed in that time frame from now on.

Whatever is decided, I fully agree with the author that convergence is very important. Piecemeal releases by the big guns would hurt Bordeaux. Commercial efforts need to be coordinated.