It is so easy to criticize, to come onto the scene after the fact and tell others what they ought to have done – to be, as the French say, un inspecteur de travaux finis… This is very tempting with the 2019 en primeur campaign, which is navigating in uncharted waters and progressing in a way that is not always easy to understand. However, the corina virus pandemic has necessarily imposed a radical departure from past campaigns, and the powers-that-be in Bordeaux are reacting as well as they can.

There are three main dilemmas facing the 2019 vintage today.

The first involves the barrel tastings of the new vintage. For many years, these have taken place in late March/early April and have been a resounding success, like nothing else in the world of wine. Wine professionals from all over the world routinely attend. The problem this year is that the tastings had to be cancelled in extremis.

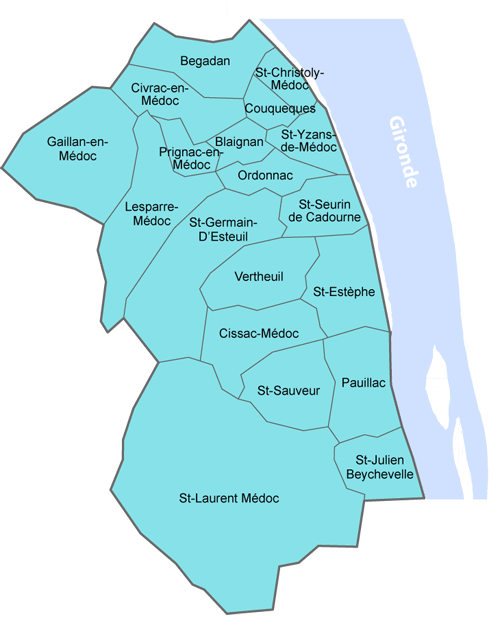

Château owners have decided to rebound as best they can. For instance, a mammoth tasting of the 2019s will be held in Bordeaux on the 5th of June for some 450 French négociants, brokers, and journalists. In addition, the Union des Grands Crus will host tastings in Paris, Brussels, Zurich, and Hong Kong (none planned so far in London or New York). The famous châteaux will welcome visiting professionals starting in June, but will be taking every precaution: social distancing, gloved staff, disinfection, groups limited to 8 people, etc.

This response is to be admired, and once again proves the resiliency of the Bordeaux wine trade. However, it is not without its problems and challenges.

The networking that is part and parcel of the en primeur tastings will be sorely missed. Foreign buyers travel to Bordeaux not just to taste hundreds of wines like robots. They also come to learn about the state of the market, as well as to meet producers, merchants, competitors, etc.

There is a technical aspect to this as well. What about wines sent abroad and the conditions under which they are tasted? Samples are refreshed every single day at the en primeur tastings in Bordeaux. But what about those in foreign capitals?

As opposed to group tastings organized by the Union des Grands Crus, individual châteaux are also sending a scattering of samples to clients and noted critics. If these arrive very shortly after shipment, there is, of course, no reason they cannot be professionally evaluated. However, the whole point of en primeur tastings is to compare wines! If four châteaux from, let’s say, Saint-Julien send samples, which arrive on different days and are tasted separately, an extremely important frame of reference has been eliminated. Results are biased. And if the four samples are kept back to be tasted together, they will not be in the same condition.

I agree with many of my friends in the wine business that it would have been a better idea to hold the tastings in Bordeaux in September rather than June in light of the many restrictions currently weighing on all events involving groups of people. In fact, it was earnestly hoped in some quarters that the en primeur tastings would “skip a year”, and take place in early 2021 (before bottling), thereby setting a precedent. The advantage here is that the wines would be much further along and therefore a much truer reflection of their ultimate quality.

The argument against this, of course, is that château owners have become used to pocketing payment in the spring following the vintage and that delaying this by months or, worse still, a full year, would constitute a huge handicap. Does this hold water? While many estates have to finance major investments, i.e. repay debts, it must be said that, by and large, the great growths are in a very sound financial situation – in fact, quite a priviliged one considering the plight of modest Bordeaux, in very dire straits indeed.

The second challenge facing the 2019 campaign is timing. If the tastings are being held this summer, when will the wines be marketed? September, before the harvest, seems a logical time, but no one can say for sure, which is understandable in light of the unprecedented circumstances. What is to be feared is a long, drawn-out campaign. Whether it be organizing tastings or putting wines out on the market, the Bordeaux industry has much to gain by joining forces and working together, coherently. Doing things piecemeal would only be harmful.

The third issue is, of course, pricing. We know for a fact that 2019 is a very good vintage. Detractors of Bordeaux mock such statements, and die-hard antagonists predict, for the umpteenth time, that the market will collapse, the bubble will burst, and that the elite wines of Bordeaux will be a thing of the past unless they drastically reduce their prices. We have regularly heard such forecasts through the years… However, the 2019 campaign is well and truly different. The signals from major markets are worrying. Economies around the planet are suffering and the most expensive wines are assuredly luxury i.e. non-essential products.

But let’s not dramatize the situation! If there are no takers for the grands crus at the prices being asked, those prices will come down. It’s as simple as that. President Calvin Coolidge famously said “The business of America is business”. This is true of Bordeaux too, and a realistic response would occur in short order. While it would be humbling to have to go back and bring down prices, the region has seen numerous crises through the centuries and can cope quite well, I am sure.

So, while not exactly sitting on the edge of my seat, I am quite intrigued to see how the campaign will go this year. Care must nevertheless be taken not to misinterpret information and fall prey to fake news. For instance, while such and such a château may “come out” at a given price, that first tranche price may be just to test the water and involve only a small part of production. It could be totally misleading and unrepresentative. By the same token, you may hear, as I have, that the cellars in Bordeaux are bursting at the seams with unsold wine. This, too, must be taken with a grain of salt because the situation varies enormously among hundreds of châteaux. So, no pontification, please.

In any event, few critics’ scores will be trustworthy in my opinion for the reasons outlined above. So the parameters for setting prices may well change. Those rare critics who have travelled to Bordeaux and tasted across the board will undoubtedly have greater influence.

I wrote this text on the 27th of May in the morning and by late afternoon I had received my first offer to buy wines from the 2019 vintage: Arsac, Beaumot, Lannessan, and Tertre Roteboeuf.

When will the big guns come out? Your guess is as good as mine…

2020 is decidedly a very atypical year for Bordeaux – as it is for the rest of the world.