Boyd Cantenac

N: Fresh and pure with brambly overtones. Subtle.

P: Rich and chocolatey, with high-quality tannin. In a very classic mold. Very good.

Brane Cantenac

N: Strong, toasty oak and roast coffee aromas predominates at this point, somewhat hiding the fruit.

P: A different story on the palate, with a lovely, soft, caressing mouth feel and great purity leading into a long mineral aftertaste. Considerable delicacy and elegance, i.e. very Margauxlike. Great, long, cool aftertaste. Very good.

Cantenac Brown

N: Lovely floral aromas along with sweet black fruit nuances.

P: Medium weight, but oh so soft… Great balance. Svelte with fine acidity. Long textured aftertaste. Gives every indication of delivering much at an early age. Very good.

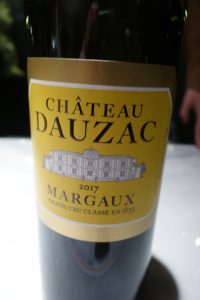

Dauzac

N: Bit dank, closed-in, and lacking focus. Penetrating in an odd way with a noticeable alcoholic presence. Not positive at the present time.

P: Better, with an inky palate and upfront fruit. Vibrant acidity with a medium-long, slightly dry, and definitely oaky aftertaste. A more commercial style. Good.

Desmirail

N: A little one-dimensional with plenty of oak, although this may well integrate over time. Some blackcurrant, black olive, and mint/eucalyptus aromas.

P: Lively and fruity, but somewhat hard. Better than in recent vintages. Tangy, fresh finish. Watch out for the rest of barrel ageing so as not to overwhelm the wine. Potential sleeper. Good.

Durfort Vivens

N: Menthol aromas overlaying blackcurrant, along with some polished wood overtones.

P: Starts out soft, then goes on to show considerable tannic backbone. Assertive aftertaste with velvety texture. Somewhat old school. Some dryness on the finish. Needs to digest the oak. Good.

Ferrière

N: Lovely, well-integrated oak. Ripe, but not overripe, with berry fruit. Slight greenness, but this does not detract. Subtle coffee and blackberry aromas.

P: Refreshing and lively. Pure, but somewhat short. Attractive mineral aftertaste, but lacks personality on the middle palate as well as richness. A light Ferrière. Good.

Giscours

N: Berry fruit (perhaps a little jammy) along with interesting floral (iris, jasmine) nuances.

P: Rich attack going into an oaky roundness with not much going on in between. Margaux characteristics there, but the oak comes across as really overdone at this stage. Needs retasting to form a valid opinion. OK

Issan

N: Muted. Some polished wood aromas.

P: Very soft and velvety. Lively and classic. Lovely vibrant fruit but on the simplistic side. Unquestionable finesse. Good to very good if the bouquet blossoms.

Kirwan

N: The fruit is not overshadowed by the oak, but there is not much there.

P: Medium-heavy mouthfeel but rather diluted on the middle palate. However, the powerful, long aftertaste bringing up the rear saves the day. This is vibrant, velvety, and characterful. Obviously needs time to come together. Somewhat of a liqueur/spirity aspect. Good.

Lascombes

N: Coming out of a dormant period with some original graham cracker, liquorice (zan), and chalky aromas.

P: Starts out rich, fruit-forward, and enveloping… and then drops. Shortish aftertaste. Going on round, then segues into a hard aftertaste. OK.

Malescot Saint-Exupéry

N: Muted, slightly alcoholic.

P: Lovely and soft, but with a decided tannic presence and good acid backbone as well. Good balance and cool, long aftertaste. An elegant Médoc. Good.

Margaux

N: Softly penetrating inimitable trademark bouquet. Fresh, elegant, crystalline.

P: Striking silky quality going on to show a lovely acid backbone. Not big, but velvety and super long. Not monumental, but excellent.

I also tasted the white wine, Pavillon Blanc, which I normally speaking wouldn’t mention here, but this vintage is nothing short of extraordinary. Extremely poised and aromatic, with a finish that goes on and on. The best white Margaux I’ve ever had (there have been a number of hits and misses…) and one of the best white Bordeaux I’ve been privileged to taste as well. Great success.

Marjolia

N: Closed (at this early stage, of course) with more beeswax and oak than fruit.

P: Fortunately much better on the palate. Ripe fruit, yes, but far too oaky. Good, but nothing special.

Marquis d’Alesme

N: Attractive dark fruit underdeveloped at this time. Some toasty oak.

P: Silky, layered attack, then drops. A natural, fresh wine with well-integrated oak, but short. Good.

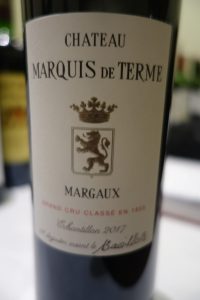

Marquis de Terme

N: Lovely blackberry liqueur and blackcurrant aromas. No terribly complex, but seductive. Oak as it should be.

P: A little dilute, and somewhat hollow, but this is a vinous crowd-pleasing sort of Médoc that will be enjoyable young. Good.

Palmer

N: Lovely sophisticated nose of candied red and black fruit

P: Rich, a little spirity, with some tarriness, and develops beautifully on the palate. Tremendously long, seductive finish. Velvety texture. Very good.

Prieuré Lichine

N: Unusual, wild, New World type aromas. Not typical of its origin or seemingly of its grape varieties. Intriguing, almost Grenache-like bouquet!

P: Thickish texture and melts in the mouth. Starts out quite rich and spherical, and then drops, nevertheless going into a good mineral aftertaste. Off the beaten track. Will show well young. Marked oak on the aftertaste should integrate. Good.

Rauzan Gassies

N: Light, attractive, typical Margaux bouquet.

P: Watery, but goes into a decent aftertaste. Better than many other previous vintages. OK

Rauzan Ségla

N: Fine, polished, sweet Médoc nose of blackcurrant. Not overoaked. Haunting. Not pronounced.

P: Medium-heavy mouth feel. Satin texture and finishes with an attractive minerality. Quite round for its appellation. Light on its feet with a fine velvety aftertaste. Very good.

du Tertre

N: Off smells. Some stink. Not showing well.

P: Bretty quality carries over to the palate, which also displays loads of oak that overshadows the fruit. This may be just a difficult phase, or a bad sample.