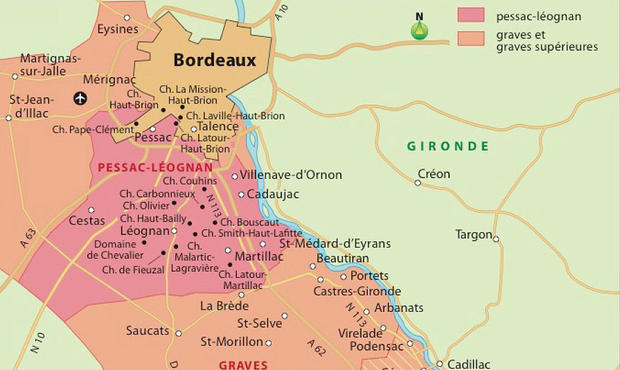

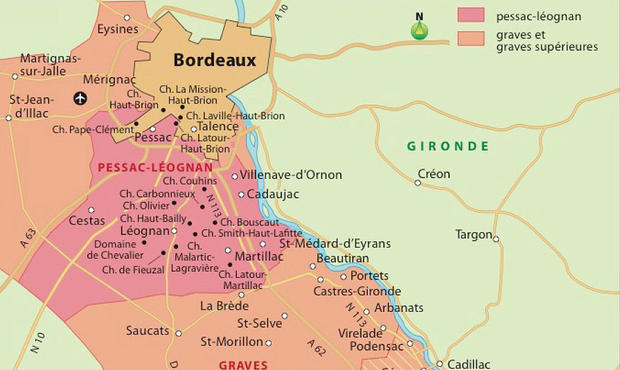

To give you an idea of how old I am, I can remember a time when the Pessac-Léognan appellation did not even exist. All the wines on the left bank of the Garonne southeast of Bordeaux were Graves. Period. The new appellation was created in 1987 after a sort of “civil war” between north and south. The northern part of the Graves, bordering on the city of Bordeaux, encompassed all the great growths (seven reds, three whites, and six both white and red) in ten different communes. There was some disagreement as to where to draw the borders of the new entity and even what to call it. After much discussion and negotiation, the hyphenated names of Pessac and Léognan were retained.

Interestingly, the great growths continue to call themselves crus classés de Graves, even though they are all in Pessac-Léognan…

The late André Lurton of Châteaux La Louvière, Couhins Lurton, Rochemorin, de Cruzeau, etc. was a prime mover in creating the new AOC.It must be said that other than recognizing an élite within the Graves, the establishing of Pessac-Léognan also helped the region to fight urban sprawl seriously threatening prime vineyard land. The area under vine had dwindled to just 500 hectares by 1975, but now stands at 1,600.While many English-speaking wine lovers tend to associate the Graves with white wines, Pessac-Léognan produces 75% reds.

The Bordelais have a special fondness for Pessac-Léognan. The vineyards start at the outskirts of the city. Indeed, the postal address of Château Les Carmes Haut Brion, for instance, is 20 rue des Carmes, Bordeaux. However, the wines are also popular because they frequently represent better value for money than ones from the Médoc or Saint Emilion, and because they have the faculty of showing well both young and old. Pessac-Léognan wines are frequently found in local restaurants at an affordable price.

As those of you who follow this blog know, I am a great fan of the Portes Ouvertes (Open Days) in Bordeaux, when châteaux welcome the general public. This is a wonderful opportunity to visit little-known estates and make discoveries.

-

-

So I set out on a Saturday with two friends in early December to visit thirteen estates in one day – a wonderfully intense, relatively frenetic, and very pleasurable learning experience.We started with Château Luchey Halde in the town of Mérignac, a suburb of Bordeaux where the airport is located. This 23-hectare estate had altogether disappeared, but was miraculously brought back to life and replanted in 1999. It is now owned and managed by an agricultural engineering school, Bordeaux Science Agro (ex-ENITA). The winemaking facilities are, as to be expected, very modern and well-maintained. There was some discussion at the beginning of the tasting whether we should try the whites before the reds or vice versa. It is usual in Bordeaux to begin with reds, a practice to which I subscribe. So we went through the 2018 (grand vin), 2015 (second wine, Les Haldes de Luchey), 2012 (grand vin), and 2011 (grand vin) reds, with a preference for the 2018 and 2012. The other two vintages seemed pleasantly fruity, but somewhat weak. Next up were the whites, 2014 (second wine) and 2012 (grand vin) which were aromatic and angular.

-

-

Owned by the Calvet family, who gave their name to a famous Bordeaux négociant firm, Château Pique-Caillou is a stone’s throw from Luchey Halde. It is quite something to visit a château dating from the late 18th century in the middle of 20 hectares of vines completely surrounded by suburban houses – not unlike Haut Brion. We sampled three red wines: 2018, 2016, and 2015. The 2016 stood out and all three showed a lean, classic style on the early-maturing side. The 2017 white Pique Caillou was practically transparent with some lanolin and vanilla nuances on the nose. The wine was light and mineral on the palate.

-

-

The third estate we went to was Château Haut Bacalan in Pessac (8 hectares), a first for me. This is owned by the Gonet family from Champagne, along with several other Bordeaux vineyards, including Château Lesparre in the rather esoteric Graves de Vayres appellation. All of the Gonet wines were being poured, including their Champagnes, but I focused on just two of their five Pessac-Léognan estates. The red 2015 Haut Bacalan showed lovely sweet briary fruit on the nose. It was powerful, full-bodied, and rich, with textured tannin on the palate – one of the nicest wines we tasted all day. The 2014 red was not quite in the same league, but nothing to sniff at either. This was followed by the 2018 white wine from Château d’Ek. Anyone who has travelled from Bordeaux to Toulouse has noticed this beautiful medieval (12th century) château quite close to the motorway. I had very much enjoyed their 2010 red wine recently (it was the Cuvée Prestige), so was anxious to try the white wine, made with 100% Sauvignon Blanc. This had a subtle bouquet of peach and talc, and lacked only a little richness on the palate.

Château Brown in Léogan takes its name from John Lewis Brown, a Scottish wine merchant who owned the property in the late 18th century. It now belongs jointly to the local Mau family and Dutch businessman Cees Dirkzwager (also co-owners of cru bourgeois Château Preuillac in the Médoc). Brown is managed by the dynamic Jean-Christophe Mau, whose family have been négociants for five generations. His wines are expertly made and a joy to drink. As much as I like the red wine (the 2015 we tasted is no exception), produced on 26 hectares of vines, my heart has always gone out to the exuberant, rich, white wine (5 hectares), everything a fine white Graves should be. I bought a bottle of the latter for the cellar.

Domaine de Grandmaison (19 hectares) is close to the Centre Leclerc supermarket – with one of the finest wine selections in the region – as well as Château Carbonnieux. I have been here on several occasions and find the wines excellent value for money. Although the 2014 red was slightly rustic and disappointing, the white has never let me down. 2018 Domaine de Grandmaison white, selling at 16 euros a bottle is a vibrant, fresh, pure wine that would grace any table. While not quite as “serious” a wine as Château Brown or some others, it is nevertheless the perfect illustration of how good affordable Bordeaux can be. Especially when one thinks of the cost of white Burgundy…

Number six on our day out was Château Haut Plantade in Léognan (9 hectares), a worthwhile discovery for me. This ten-hectare estate produces mostly red wine. We tasted the 2017 red, not the greatest vintage, during which they lost half the crop due to poor weather conditions. That having been said, apart from a slight greenness, this was a very creditable effort. The 2018 white wine (50% Sémillon, 50% Sauvignon Blanc) was very suave and subtle with a long aftertaste. It was definitely one of the best wines tasted all day. Winemaker Vincent Plantade is switched-on and funny. So, I would definitely put this château into the category of “little-known gems I would like to get to know better”. I stopped and looked at the vines upon leaving. The fine gravel topsoil seemed the perfect illustration of Graves terroir…

-

-

-

Le Manège restaurant at Ch. de Léognan

-

Our next visit was to Château de Léognan (6.5 hectares) in the town of the same name, not far from Domaine de Chevalier. Going here served two purposes since there is also a good bistro-type restaurant there called Le Manège. After a very enjoyable lunch, we went to taste the wines. I wish I could be more positive about them… We sampled two reds, 2015 La Chapelle de Léognan (the second wine) and the 2011 grand vin. The former was somewhat herbaceous and prematurely old, and I’m sorry to say that the latter did not leave much of a better impression. A 2018 white wine (AOC Graves) called simply “Le Blanc” (AOC Graves) was also poured. This was sound, but not noteworthy.

-

-

Château Haut Lagrange (8.5 hectares), likewise in Léognan, provided a better experience. We tasted four wines here. The 2016 red had an intriguing bouquet and a promising profile while the 2015 red featured a floral nose with a certain smokiness, accompanied by richness and sweet fruit on the palate. The 2006 red looked considerably older than its age with tertiary gamey notes and finished a tad dry. The 2018 white was fresh and classic, but lacked personality.

-

-

Our ninth visit of the day was to Domaine de la Solitude in Martillac. This is owned by nuns belonging to the order of the Holy Family and managed by Olivier Bernard of Domaine de Chevalier. The 32-hectare estate has quite a reputation for good reasonably-priced wines, which explains why the tasting room was thronged and people were walking away with full cartons. We tasted four wines. The 2016 red was in a seductive commercial style with upfront fruit. The 2015 displayed elegant understated aromatics accompanied by a soft mouth feel backed up by good tannin. Both of these wines are probably best enjoyed relatively young. The 2016 white had a classic bouquet with good oak, and was perhaps better on the nose than the palate. The 2010 had aged well, with floral and beeswax nuances and only a touch of oxidation.

We went from there to Château Mirebeau, a small (5 hectare) estate in the town of Martillac. Sometimes you just have to be honest. I am not reproducing my notes because they are extremely critical. We tried the 2016 and 2015 reds and they seemed flawed. The wine is made organically which is obviously a plus, but not enough. Organic wines need to be good as well.

Our next stop was at Château Ferran, also in Martillac. I’ve rarely seen the wine, which is surprising since the estate is by no means small (19 hectares). It has been in the same family for five generations and boasts an attractive château. We tried three wines. The 2016 red was very promising with good acidity and an attractive mineral austerity. The 2015 red had a rich bouquet of candied red fruit even if it was somewhat one-dimensional on the palate. The 2018 white had a nose that screamed Sauvignon Blanc, and proved to be rounder than expected. I came away with a fine memory of our visit.

-

-

The next to last château was Bouscaut in Cadaujac, a large (47 hectare) classified growth owned by Sophie Lurton and her husband Laurent Cogombles. The 2016 red Bouscaut was unquestionably of cru classé quality: smooth and assertive, with tight tannins, violet overtones, and good length. The 2015 red was unfortunately not in the same mold. It showed more toasty oak on the nose than fruit. It was brawny, big, and hot on the palate, lacking the elegance of the 2016. Then it was on to the whites. The 2017 Les Chênes de Bouscaut (a much better year for Bordeaux whites than reds) had a spicy component and was quite classy, whereas the 2016 had unusual vanilla and matchstick aromas reminiscent of white Burgundy! It was in a modern, commercial style on the palate and I will be interested to see how it ages.

-

-

The final stop of a very full day was at Château Baret in Villenave d’Ornon (24 hectares), which has been in the Ballande family since 1867. Once again, we tried both the red and white wines. The 2015 red was a good middle of the road Pessac-Léognan with a tangy flavor. It was unexpectedly tannic on the finish, but time will surely soften the rough edges. The 2011 had minty old library aromas. It was fully evolved on the palate with a somewhat hard finish. Time to drink up.

And thus ended our excursion.